For nearly 22 months, the COVID-19 pandemic has forced a shift in research focus to the SARS-CoV-2 virus. However, other deadly viruses, such as HIV (human immunodeficiency viruses) and Ebola, continue to pose a threat. A new study suggests that a gene found in monkeys and mice may work as a new type of antiviral to block such viruses, which is encouraging news for treating diseases caused by such viruses.

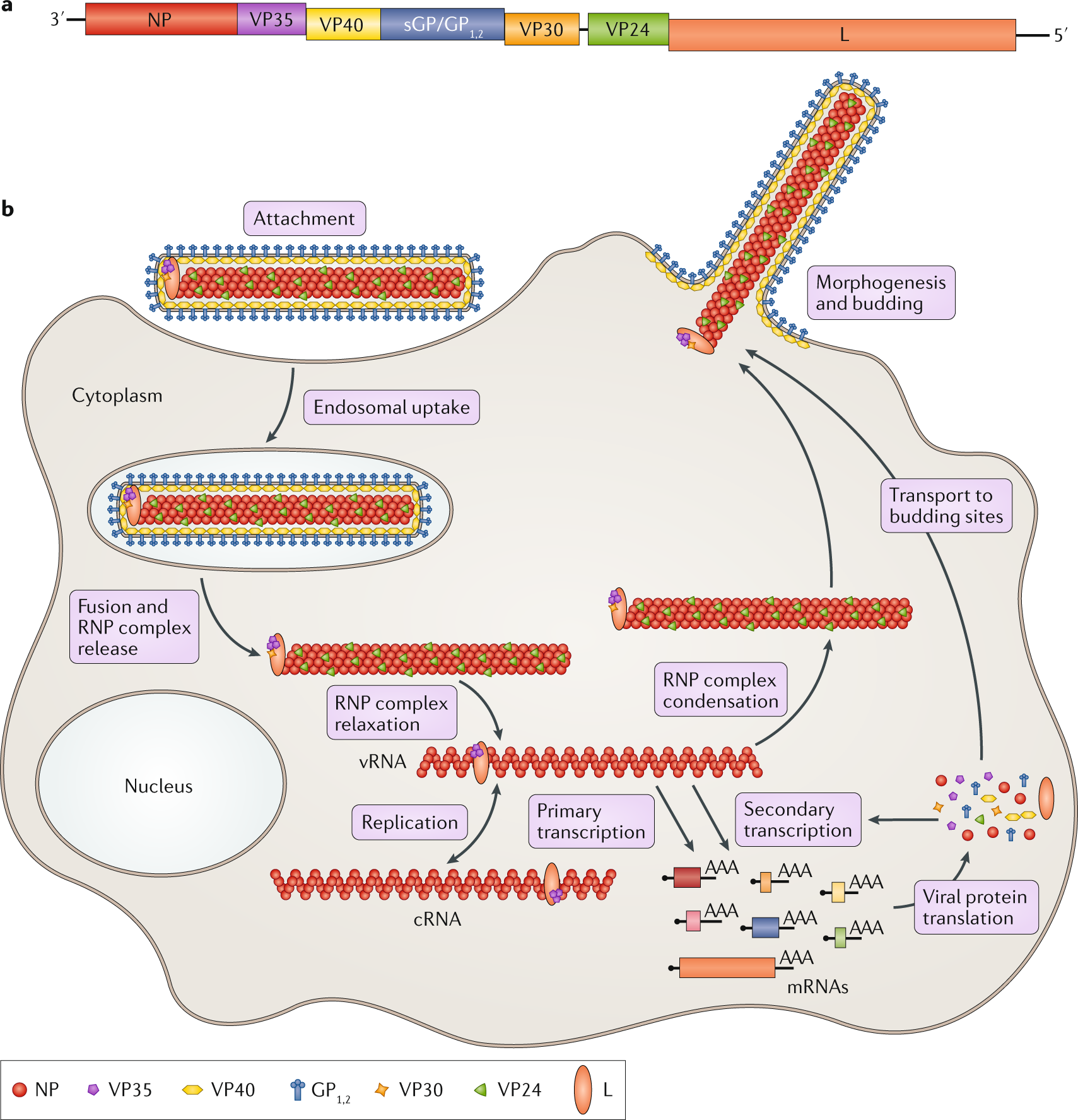

A mutated gene—retroCHMP3—naturally found in certain animals, according to a new multi-institutional study, may help stop the spread of HIV and other viruses from infected cells to healthy ones. RetroCHMP3 inhibits viruses’ ability to leave infected cells by delaying a critical process known as budding. The researchers demonstrated that causing human cells to produce retroCHMP3 can prevent viruses from infecting them from exiting. Enveloped viruses are known to be encased within their cell membranes. They leave the host cells by budding off. RetroCHMP is a gene that delays this process long enough to ensure that the virus does not escape the host cell, preventing it from infecting other cells.

RetroCHMP (or other variants) is found in certain species of monkeys and other animals and is derived from a duplicated copy of a gene known as charged multivesicular body protein 3 (CHMP3). Humans, on the other hand, only have the original CHMP3. CHMP3 is involved in cellular processes such as cell division, intercellular signalling, and membrane integrity maintenance in humans and other animals. Taking Control of a Critical PathwayUnfortunately, viruses such as HIV hijack this specific pathway, known as the ESCRT (endosomal sorting complex required for transport).

This allows them to break free from the cell membrane and infect other cells. The team hypothesised that duplications of CHMP3 observed in mice and primates prevented this from happening as a means of protection against viral diseases such as HIV based on their findings. Using this as a starting point, the authors began investigating whether retroCHMP3 variants could be used as an antiviral. In unrelated studies, a modified shorter form of human CHMP3 was found to successfully prevent HIV from budding off infected cells.

They were, however, constrained by a limitation: the altered protein ended up disrupting vital cellular functions, resulting in cell death.

Virus Exit PreventionFortunately, the researchers had access to naturally occurring variants of CHMP3 derived from other animals. They took a different approach with this. The scientists used genetic tools to induce human cells to produce the form of retroCHMP3 found in squirrel monkeys.

The cells were then infected with HIV. It was discovered that the lethal virus struggled to break free from the cells. In other words, they prevented them from leaving the cells and thereby preventing their spread. It is worth noting that metabolic signalling was not disrupted during this process. Cellular functions were not disrupted, which can result in cell death.

“We’re excited about the research because we previously demonstrated that many different enveloped viruses use this pathway, known as the ESCRT pathway, to escape cells. We had always suspected that this was a point at which cells could defend themselves against such viruses, but we couldn’t see how that could happen without interfering with other critical cellular functions “Dr. Wes Sundquist, a co-corresponding author of the study, emphasised this. Possibility as a Treatment OptionAccording to Dr. Elde, these findings suggest a novel type of immunity that can emerge quickly to provide protection against short-lived threats.

“We thought the ESCRT pathway was a weakness that viruses like HIV and Ebola could always exploit as they bud off and infect new cells. RetroCHMP3 flipped the script, exposing the viruses.

Moving forward, we hope to learn from this experience and apply it to combat viral diseases “Dr. Elde elaborated.

The study’s most important finding was that slowing down certain cellular functions can prevent cell damage. Dr. Sanford Simon, co-author of the study, concluded that “raises the possibility that an intervention that slows down the process may be insignificant for the host, but provide us with a new anti-retroviral.”

___________

Monkey | Don’t forget to follow us on Twitter @njtimesofficial. To get the latest updates