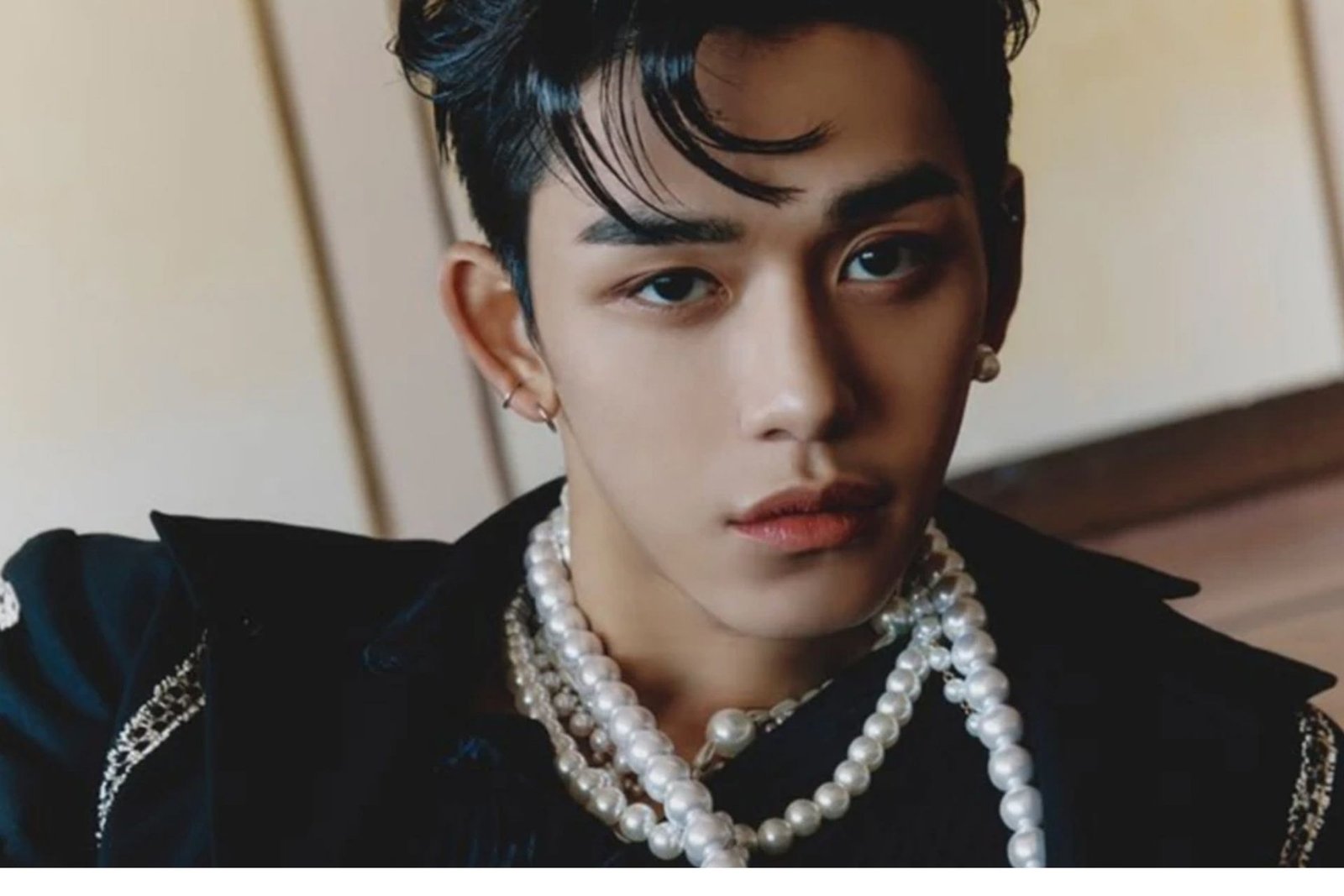

The main thing you should think about the late Marcel Theo Hall, better referred to the world as the rapper Biz Markie, is that he had a music profession that couple of have completely wrestled with.

Business could do anything: beatbox, record-scratch with his mouth, sing at odds with feeling and intensity, and appear the best emcees of his day, all through sheer energy and character.

During the 1980s, as rappers came to mark themselves per melodious ability or road smarts, Biz separated himself from that period’s rhyme specialists and hawkers and socially cognizant evangelists—he rather showed a numskull who actually deserved all your admiration.

Business could stand his ground with Big Daddy Kane or Heavy D; he affected everybody from Biggie Smalls to Anthrax; he could give a growling snare to Jay-Z or do the most upbeat Elton John cover you’d at any point heard; he could turn unremarkable tunes by ’70s rock staples like Ted Nugent and Gilbert O’Sullivan into gold.

All through everything, he stayed receptive, self-destroying, and entertaining, somebody strangely OK with finding himself in a tough spot and his finger in his nose while in a public restroom.Biz Markie—who kicked the bucket Friday, July 16, of Type 2 diabetes and at an appallingly youthful age, as so numerous others of his age—was a unique, multi-layered inventive in a way the individuals who know him mostly as the “Simply a Friend” fellow have never completely figured it out.

That is a disgrace, on the grounds that the Biz’s heritage across rap music is definitely more critical than most advanced devotees of the class even know. (Try not to misunderstand me—”Simply a Friend” is an incredible, exemplary melody, and the explanation it remains so cherished is on the grounds that it’s Biz at his best.

In any case, it’s not the awesome Biz.)Biz Markie’s vocation started where so numerous other hip-jump greats’ did: in the clubs and rear entryways of Reagan-period New York, where he consummated his vocal percussion and rhymes and turntable twists before crowds progressively while following the road artists quickly springing up around him.

As he told the Washington Post Magazine in 2019, his moniker didn’t begin from German Chancellor Otto Von Bismarck, as many may have accepted; all things considered, it came from spearheading rapper Busy Bee Starski’s stage name, which Marcell Hall attached to his youth Long Island area epithet, Markie—he was in every case all the more profoundly receptive to his city and its expanding creative scenes than to whatever else.

While hip-jump turned into a substantially more intense melodic power all through the ’80s “brilliant age,” Biz tracked down a home with the Juice Crew, the amazing Queens-based rap aggregate drove by DJ Marley Marl that delivered figures like Kool G Rap and Masta Ace and prompted a portion of rap’s most significant early cuts.

But as Biz’s countrymen adopted more fierce strategies in the scene, from the supposed Bridge Wars to “Roxanne’s Revenge,” he displayed himself on his 1988 presentation, Goin’ Off, as a beatboxer, affront comic, nose-picker, and narrator who could catch the core of New York City.

Maybe no finer model exists of his vast creative mind than the LP cut “Fumes,” in light of a meaning of the nominal word Biz thought of himself (“The meanin’ of this word, without no question/Means no one need to be there when you’re out for the count/Once you’re set up and got a ton of cash/Everybody wanna be your mate and nectar”).

“Fumes” not just communicated an idea natural to rappers recently effective in the consistently developing classification, yet it likewise recounted genuine accounts of individuals in Biz’s circle, from snare man TJ Swan to tune co-author Big Daddy Kane, from DJ Cutmaster Cool V to Biz Markie himself.

It was forthright, individual, and surprisingly defenseless (“After getting dismissed I was extremely discouraged/Sat and kept in touch with some def doo-doo rhymes at my rest”); it was additionally appealing and all inclusive.

Business’ idea of “fumes” would enter the rap vocabulary, however the melody would be referred to and tested by rappers consistently, with the Biz-wrote line “Damn, it feels great to see individuals up on it” showing up word for word in tune after tune (Snoop Dogg would completely cover “Fumes” in 1997 and afterward in another remix in 2017).

After Goin’ Off hit the Billboard diagrams in spring 1988, Biz Markie would draw in additional consideration, to some degree on account of his appearance in the video for Paul Simon’s “Me and Julio Down by the Schoolyard” simply later that year.

1989 would see the arrival of The Biz Never Sleeps, which highlighted Biz’s solitary top 10 hit, “Simply a Friend,” the exemplary story of his quest for a young lady who continued brushing him off for some other person she just called a companion.

The video, including Biz cosplaying Mozart, became omnipresent to the purpose in acquiring a Beavis and Butt-Head spearing, and the tune, which would show up in film and TV soundtracks and acclaimed melodies records the world over, would be so unpreventably connected with Biz as to characterize his eulogies and communications with regular residents, who right up ’til the present time botch him for a one-hit wonder.

After the “Simply a Friend” frenzy, Biz delivered I Need a Haircut in 1991. This LP wasn’t just about as fruitful as Biz’s previous two, yet it became famous in rap history for the track “Alone Again,” which tested the treacly father rock top choice “Alone Again (Naturally)” by Gilbert O’Sullivan without consent (however, as Oliver Wang wrote in 2013.

Biz and his mark attempted to clear the example with O’Sullivan, just to be turned down; the difficulty came when they delivered the melody in any case).

The year Haircut came out, O’Sullivan sued Biz in a milestone claim that would perpetually move the scene of hip-bounce: The appointed authority decided for O’Sullivan, banning Cold Chillin’ Records from selling all things considered “Alone Again” or Haircut and alluding the supposed example robbery to criminal court (which was dropped).

As I composed back in 2019, that case, alongside musical crew the Turtles’ example based suit against Biz’s crackpot counterparts De La Soul, cooled the fate of test substantial hip-jump, moving away from the reorder sound arrangements of gatherings like Public Enemy and toward more cautious, limited style.

The decision likewise, similarly as troublingly, kept heap different melodies from truly being authoritatively delivered. Right up ’til today, you can’t pay attention to quite a bit of either De La Soul or Biz Markie’s initial inventories on web-based features, putting a significant number of their works of art far off in a Spotify-overwhelmed music economy.

De La Soul has attempted on numerous occasions over the course of the a long time to guarantee more pleasant terms for the advanced arrival of their music, including by showing up on the animation Teen Titans Go! simply recently; Biz would shamelessly deliver a collection named All Samples Cleared! in 1993, however he seldom put forth other correspondingly open attempts to get his more seasoned collections on advanced stages.

(You can lay out almost $200 to get a vinyl squeezing of The Biz Never Sleeps from Amazon, however.)

The most significant thing about the Biz, a long way from simply his hits, his legitimate difficulties, his business gigs, is this: He was an altogether unique sort of rapper, an interesting and adaptable presence we’re not prone to see again, a symbol of a long-time long since past.

Relatively few other outdated rappers could pull off his demonstration of both lewd unconventionality and wide-running vocal and melodic ability that he could take to any medium.

Business became part of the gang who could show up all over and no place, as the (moans) “Simply a Friend” fellow, or the peculiar beatboxing fella in the entirety of your number one films and shows, or the set up rapper who worked with endless legends.

He was weird and comical and all the cooler for it, agreeable in his way of life as the “jokester sovereign of hip-jump,” guaranteed in his abilities, and intense by they way he moved toward the two his music and the individuals who might dare kill at him.

Regardless of whether it was old domineering jerks who got the fumes or unoriginals like Gilbert O’Sullivan. There was no one like the Biz, whom no one could beat; it’s about time we required some investment to completely check out every one of the marvels he made.

Like he said to the Washington Post Magazine only two years prior: “The most bizarre thing about my acclaim is that when I’m imagining that it’s practically over it simply starts back up. … They’re not allowing me to pass on. The general population, the fans, they like me around.”

______________

Biz | Don’t forget to follow us on Twitter @njtimesofficial. To get the latest updates