Miranda Kelly was sick enough to be scared just a day after testing positive for covid-19 in June. Kelly, a certified nursing assistant, was 44 years old and had diabetes and high blood pressure. She was having trouble breathing, which was serious enough to send her to the emergency room.

When her husband, Joe, 46, became ill with the virus, she became very concerned, particularly for their five teenagers at home: “I thought, ‘I hope to God we don’t end up on ventilators.'” We have a family. “Who is going to raise these children?”However, the Kellys, who live in Seattle, agreed to participate in a clinical trial at the nearby Fred Hutch cancer research centre as part of an international effort to test an antiviral treatment that could halt covid early in its course.

The couple was taking four pills twice a day by the next day. Though they were not told whether they had received an active medication or a placebo, they reported that their symptoms had improved within a week. They were back to normal in two weeks.Miranda Kelly stated, “I’m not sure if we got the treatment, but I kind of feel like we did.” “With all of these underlying conditions, I felt like I recovered very quickly.

”The Kellys are involved in the development of what could be the world’s next opportunity to combat covid: a short-term regimen of daily pills that can fight the virus early after diagnosis and possibly prevent symptoms from developing after exposure.“Oral antivirals have the potential not only to shorten the duration of one’s covid-19 syndrome, but also to limit transmission to people in one’s household if they are sick,” said Timothy Sheahan, a virologist at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill who has helped pioneer these therapies.Antivirals are already widely used to treat other viral infections, such as hepatitis C and HIV.

Tamiflu, a widely prescribed pill that can shorten the duration of influenza and reduce the risk of hospitalisation if given quickly, is one of the most well-known. The medications, which were designed to treat and prevent viral infections in humans and animals, work differently depending on the type. They can, however, be engineered to boost the immune system’s ability to fight infection, block receptors so viruses cannot enter healthy cells, or reduce the amount of active virus in the body.

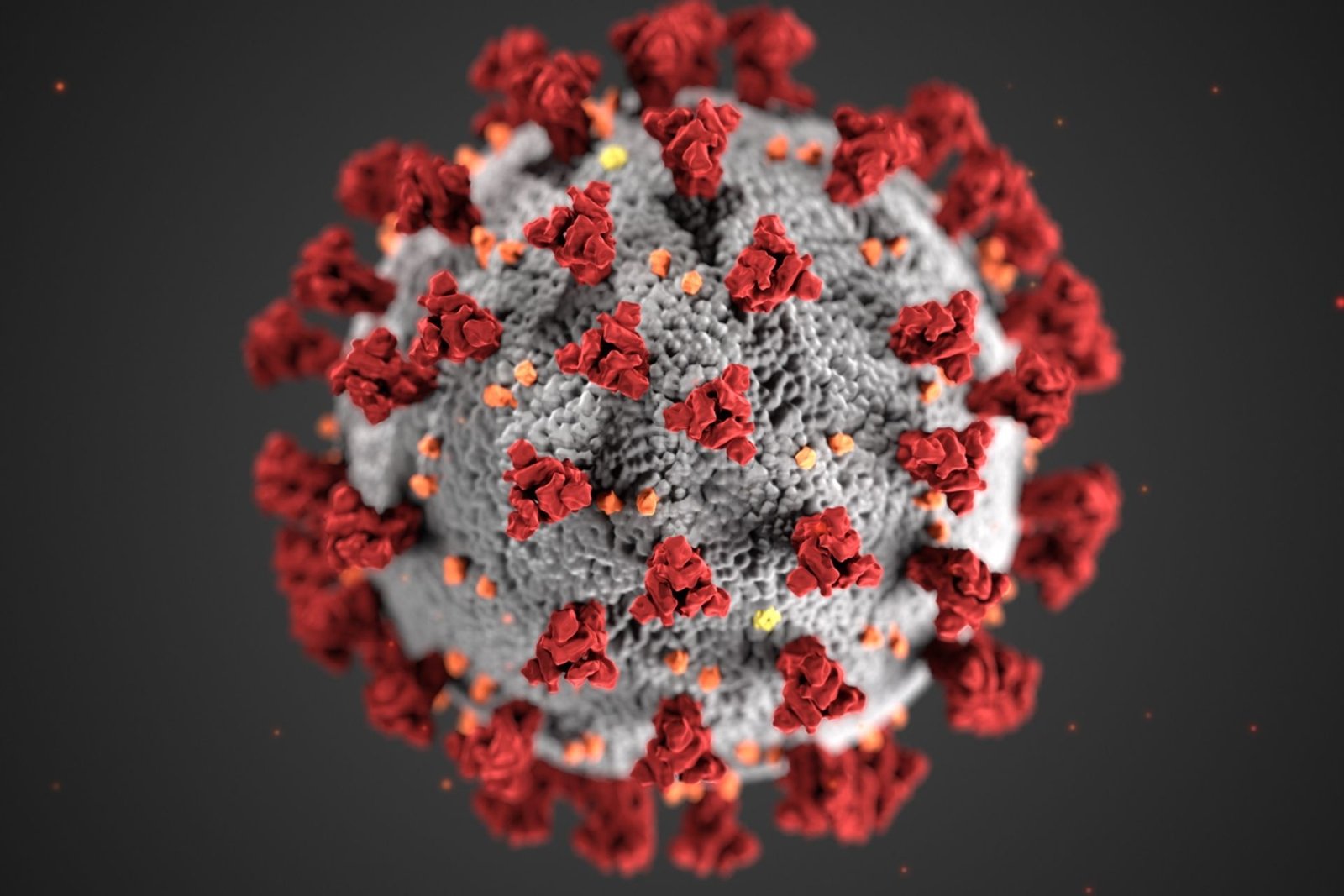

At least three promising antivirals for covid are being tested in clinical trials, with results expected as early as late fall or winter, according to Carl Dieffenbach, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases’ Division of AIDS, who is in charge of antiviral development.“I believe we will have answers about what these pills are capable of within the next few months,” Dieffenbach predicted.Molnupiravir, a medication developed by Merck & Co. and Ridgeback Biotherapeutics, is the leading contender, according to Dieffenbach. This is the product being tested in the Kellys’ trial in Seattle. Pfizer’s PF-07321332 candidate and AT-527, an antiviral produced by Roche and Atea Pharmaceuticals, are two others.They work by interfering with the ability of the virus to replicate in human cells. In the case of molnupiravir, the enzyme that copies the viral genetic material is forced to make so many errors that the virus is unable to replicate.

This, in turn, reduces the patient’s viral load, shortening the infection time and preventing the type of dangerous immune response that can result in serious illness or death.Only one antiviral drug, remdesivir, has been approved to treat covid thus far. However, it is only given intravenously to patients who are seriously ill and must be hospitalised, and it is not intended for widespread use right away.

The top contenders under consideration, on the other hand, can be packaged as pills.Sheahan, who also worked on remdesivir in the preclinical stage, led an early study in mice that demonstrated that molnupiravir could prevent early disease caused by SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes covid.

Emory University discovered the formula, which was later purchased by Ridgeback and Merck.Clinical trials have since followed, with an early trial of 202 participants last spring demonstrating that molnupiravir rapidly reduced infectious virus levels. Merck CEO Robert Davis stated earlier this month that the company expects data from its larger phase 3 trials in the coming weeks, with the possibility of seeking emergency use authorization from the Food and Drug Administration “before year’s end.”

Pfizer began a combined phase 2 and 3 trial of its product on September 1, and Atea officials said they expect phase 2 and phase 3 trial results later this year.If the results are positive and any product is approved for emergency use, Dieffenbach believes that “distribution could begin quickly.”This would imply that millions of Americans would soon have access to a daily orally administered medication, ideally a single pill, that could be taken for five to ten days following the initial confirmation of covid infection.

“When we get there, that’s the plan,” said Dr. Daniel Griffin, a Columbia University infectious diseases and immunology expert. “Having this all over the country so that people can get it the same day they are diagnosed.”Oral antivirals to treat coronavirus infections, which were previously ignored due to a lack of interest, are now the subject of intense competition and funding. The Biden administration announced in June that it had agreed to purchase approximately 1.7 million treatment courses of Merck’s molnupiravir for $1.2 billion if the product received emergency authorization or full approval.

In the same month, the administration announced a $3.2 billion investment in the Antiviral Program for Pandemics, which aims to develop antivirals for the current covid crisis and beyond, according to Dieffenbach.According to Sheahan, the pandemic rekindled a long-dormant effort to develop effective antiviral treatments for coronaviruses.

Though the original SARS virus caused scientists concern in 2003, followed by Middle East respiratory syndrome, or MERS, in 2012, research efforts slowed when those outbreaks did not last.“The commercial drive to develop any products simply went down the drain,” Sheahan explained.Antiviral drugs that are widely available would be added to the monoclonal antibody therapies that are already used to treat and prevent serious illness and hospitalizations caused by covid.

Monoclonal antibodies produced in the lab, which mimic the body’s natural response to infection, were easier to develop but must be administered primarily via intravenous infusions. Most monoclonal products are covered by the federal government at a cost of $2,000 per dose. It is still too early to tell how antiviral prices will compare.Antiviral pills, like monoclonal antibodies, would not be a replacement for vaccination, according to Griffin. They would be another tool in the fight against covid.

“It’s nice to have another option,” he commented.One challenge in developing antiviral drugs quickly has been recruiting enough participants for clinical trials, each of which requires hundreds of people to enrol, according to Dr. Elizabeth Duke, a Fred Hutch research associate in charge of the molnupiravir trial.Participants must be unvaccinated and sign up for the trial within five days of a positive covid test.

On any given day, interns make 100 calls to newly covid-positive people in the Seattle area — and the vast majority of them decline.“In general, there is a lot of mistrust in the scientific process,” Duke said. “And some of them are saying nasty things to the interns.”If the antiviral pills are found to be effective, the next challenge will be to build a distribution system that can get them to people as soon as they test positive.

Griffin believes it will take a programme similar to the one implemented by UnitedHealthcare last year, which provided Tamiflu kits to 200,000 at-risk patients enrolled in the insurer’s Medicare Advantage plans. Merck officials predicted that by the end of the year, the company would have produced more than 10 million courses of therapy. Pfizer and Atea have not provided comparable estimates.“Think about it,” Duke, who is also in charge of a prophylactic trial, said. “You could give it to every member of a household or every student in a school.

Then we’re talking about possibly returning to normal life.”Even more enticing? Antiviral studies are being conducted to determine whether antivirals can prevent infection after exposure.

________

COVID | Don’t forget to follow us on Twitter @njtimesofficial. To get latest updates