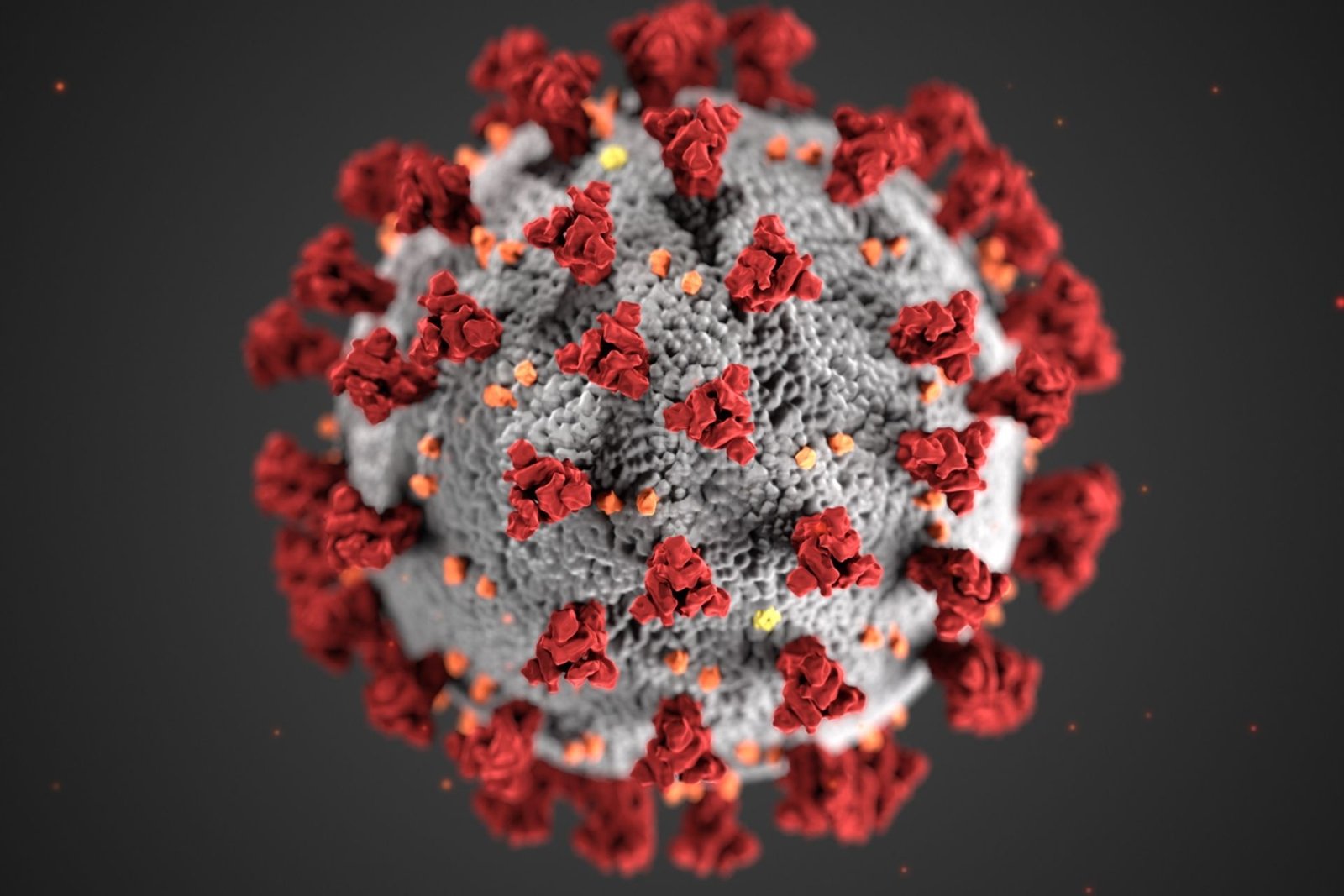

Although Texas officials stressed human rights and the economy, California’s vaccine rollout centered on equality. California and Texas, the two most populous states in the world, took vastly different approaches to the pandemic and vaccine drive to end it.

California has trumped its focus on research and policies to improve social justice.

State officials in Texas have stressed civil rights and economic security, sometimes ignoring public health alerts, but urging vaccination—while making it a personal decision.

Yet California’s dedication to equality doesn’t seem to have put the state ahead of Texas in vaccinating Latinos, who make up about 40% of both states’ population. Latinos have suffered disproportionately from COVID-19 because the poorest appear to live in cramped housing, receive less quality healthcare, and work outside the home.

In California, 22% of Hispanics were vaccinated on April 12; in Texas, 21%.

Texas, in general, did much better than California to meet extremely vulnerable populations during the first months of vaccine delivery, according to a new Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report. Texas was seventh on the list; last California sixth.

Overall, however, California’s pandemic metrics were higher. As vaccination eligibility opened on April 15, 49% of Californians 16 and older were either partially or fully vaccinated, compared to 43% of Texans.

The two states were neck-and-neck before February’s brutal winter storm took out electricity in most of Texas for a week. “We never really recovered after that, and exactly why, beyond our scale, is not entirely clear,” said Dr. Peter Hotez, dean of Baylor College of Medicine’s National School of Tropical Medicine.

California also does much more to control diseases. The average seven-day state is 52.7 cases and 1.8 deaths per 100,000 as of April 15, with an average seven-day positivity rate of 1.5%. Texas, meanwhile, has 73.3 cases and 1.5 deaths per 100,000, with an overall 7-day positive score.

State officials responded differently to those metrics. Gov. Gavin Newsom of California has set June 15 as the day to end most pandemic restrictions, barring significant setbacks, but he expects to continue to mandate mask-wearing in public and high-risk workplaces. Meanwhile, on March 10, Texas Gov. Greg Abbott authorized all businesses to reopen and lifted a statewide mask mandate.

In Texas politics, the idea of individual rights plays well and has been front and centre amid the pandemic and vaccine rollout. Though urging Texans to protect themselves from coronavirus transmission, state officials simultaneously fought the attempts of local authorities to implement such measures.

Though Newsom imposed one of the earliest and strictest state lockdowns in the country on March 19, Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton initially called local mask bans and business restrictions “unlawful and unenforceable.” Abbott eventually instituted a mask requirement and other restrictions in July after a surge of the disease. These proposals faced resistance within his own party, with Texas Republican Chair Allen West leading an October protest outside the governor’s mansion.

Against this tense political backdrop, Texas state leaders have been softer in their vaccination messaging compared with California. Both governors received their vaccinations on live TV, but each has offered different messaging about how their constituents should view the shots.

In an April 8 tweet, Abbott celebrated the state’s reaching 13 million vaccinations, adding, “These vaccine shots are always voluntary.” That soft-pedaled message also comes through in Abbott’s stance on masks. Despite order lifting in early March, the governor still encourages people to use them.

Public health experts in Texas have been frustrated by what they see as a half-hearted endorsement of public health measures. “It’s psychotic to have to listen to two very different messages,” said Dr. Andrea Caracostis, CEO of the HOPE Clinic in Houston, which serves minorities and immigrants. “Vaccines were created not only for your individual health, but for the good of the world. It’s a lesson that’s been lost in our culture.”

Newsom, on the other hand, speaks about vaccination in terms of duty to others. “Being vaccinated is a crucial move we can take to protect ourselves, our loved ones and our world and get us far closer to stopping this pandemic,” Newsom said on April 1 when he was vaccinated.

Newsom’s often-repeated “north-star” value is equity—the idea that the well-being of those most hurt by the pandemic should be central to the war. From March 4, his administration dedicated 40% of its vaccines to communities that saw 40% of COVID-19 cases and deaths. California has spent $52.7 million to support more than 300 “trusted messenger” neighborhood groups for vaccine outreach. He did not make the general public eligible until April 15 to prioritize more vulnerable and at-risk groups. Meanwhile, Texas opened the spigot on March 29.

California’s failures to vaccinate racial and ethnic minorities and the most disadvantaged, amid intense public health spending and commitment to these populations, raise concerns about state vaccine eligibility decisions, said Elizabeth Wrigley-Field, University of Minnesota’s assistant professor of sociology.

Both Texas and California, like many states, first vaccinated healthcare staff and long-term residents, majority white populations. But in Texas, people with underlying medical problems — like Type 2 diabetes, sickle cell disease or obesity — also became eligible for a shot Dec. 29.

In California, people with underlying medical problems weren’t added to the qualifying list until mid-March, and the list of underlying conditions was even more restrictive than Texas’ guidelines.

“The difference between January and mid-March, that’s sort of the storey to me,” Wrigley-Field said.

California officials agreed Jan. 13 to target citizens over 65. Many over-65 whites were at significantly lower risk than younger people of colour, said Wrigley-Field, who claims the that age-based eligibility favoured older, white populations at the detriment of younger people of colour who were more at risk of COVID-19 hospitalisation and death.

Prioritizing those over 65 automatically put Hispanics at a 2-to-1 disadvantage to whites, concluded Thomas Selden, based on research conducted with co-authors at the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (their findings don’t necessarily reflect AHRQ or HHS). Priority tiers for those with certain diseases and essential workers would have benefited the poor and Hispanics, respectively, and pushing them down the list “could be one of the factors why we’re seeing lower rates for these groups,” he said.

Hispanics aged 20-54 in California were 8.5 times more likely to die of COVID-19 than whites of the same age from March to July, according to a University of Southern California report.

In mid-February, first responders and staff in education, food and agriculture became eligible for vaccination in California. County health departments were allowed to set their own schedules, however, and they were not eligible in Los Angeles until March 1 due to insufficient vaccine availability.

In effect, from December until March there was no eligibility tier that prioritised groups that were overwhelmingly Latino or Black in the state’s largest county and the epicentre of the state’s COVID-19 cases and deaths.

The state’s approach harmed attempts to reach out to Latinos, some county health departments claim. In Kern County, Latinos made up 53 percent of the population and 57 percent of COVID-19 cases, but got just 36 percent of the vaccines administered as of April 15. Confusion over essential-worker eligibility levels led many to believe it wasn’t their “turn,” said Brynn Carrigan, director of public health county.

Dr. Tomás Aragón, State Public Health Officer and Director of the Public Health Department of California, defended the state’s initial age-based policy and said it was a tactic to ensure Latinos were prioritised. He noted that, while Latinos accounted for 48 percent of the state’s COVID-19 deaths, the majority of those deaths occurred in people over 65.

“We are in a significantly better place today than many states, not just because our vaccine strategy saved lives and kept people out of hospitals, but also because we focused on proven public health interventions, such as masking, distancing, hand washing and tracing,” Aragón said in an emailed statement.

Vaccine hesitation among racial and ethnic minorities has diminished as education has increased, access has improved, and more people see friends and neighbours safely shooting. Vaccine hesitation appears high among Republicans, particularly white evangelists, according to several polls.

But even among Republicans, trust in vaccines is increasing, according to a recent poll by Frank Luntz released by the de Beaumont Foundation. It revealed that 38% of Trump voters and 48% of Biden voters were more likely to get vaccinated than in March.

Although some experts said consistent policy messaging will be beneficial, watching friends and family safely obtain vaccinations as well as communicating with trusted individuals—especially personal doctors—is the most successful way to resolve lingering shots concerns.

“What’s going to change is making the vaccine more readily available to primary care providers… who they trust and have their questions answered because I think they’re vaccine-hesitant versus anti-vaccination,” said Dr. David Lakey, University of Texas Chief Medical Officer.

California | Don’t forget to follow us on Twitter @njtimesofficial. To get latest updates