The Governors Who Shaped New Jersey: From William Livingston to Phil Murphy

A 250-year journey through the leaders who redefined New Jersey politics, from revolution to modern progressive battles.

Trenton, September 7 EST: The story of New Jersey’s governors is, in many ways, the story of the state itself stubborn, improvisational, full of sharp turns. Since the Revolution, Trenton has seen leaders who rewrote constitutions, built turnpikes through farmland, slashed taxes, raised them just as quickly, and argued about what it meant to make life affordable in one of the most densely populated places in America.

It begins, as it must, with a lawyer in a wig standing in the middle of a war.

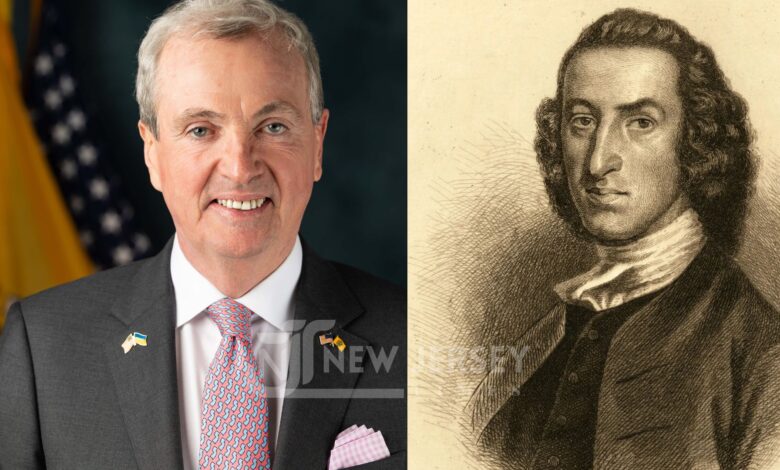

A State Born in Crisis William Livingston, 1776–1790

When William Livingston took the oath as New Jersey’s first governor in August 1776, the British army was marching through New York. The Hudson River was filled with warships. New Jersey, a contested strip of farmland and rivers between two colonial capitals, was suddenly on the front line of a revolution.

Livingston wasn’t a war hero in the mold of Washington. He was an intellectual, a pamphleteer, a man who had already made enemies with his pen. What New Jersey needed was someone who could give legitimacy to a brand-new constitution and hold the state together as militias skirmished across its fields.

He lasted 14 years, which in that era was remarkable. Livingston steered the state through occupation, tax disputes, and the grinding work of proving that a fledgling state could govern itself. Rutgers historians point out that his real achievement was continuity. By dying in office in 1790, he had given New Jersey something priceless in an unstable time predictability.

Still, the office he occupied was weak. Governors were checked by the legislature, hemmed in by short terms, and expected to bow to party bosses. For more than a century, New Jersey’s governors were caretakers, not powerhouses. That would not change until the mid-20th century.

The Long 19th Century Weak Governors, Strong Machines

In the decades after Livingston, New Jersey politics fell into the grip of county bosses and legislative barons. Governors came and went, often serving one-year terms, some stretching to three. Their names rarely stuck in the national memory.

This wasn’t accidental. New Jersey’s 1844 constitution gave the legislature control and deliberately kept the governor’s power thin. That meant railroads, industrial barons, and later party machines could dominate policy.

It also meant the state entered the 20th century without the kind of executive leadership seen in New York or Pennsylvania. Governors were often remembered less for what they did in office than for what they did after leaving it. Woodrow Wilson, for example, used his 1911–1913 governorship mainly as a stepping stone to the presidency.

By World War II, frustration with this arrangement had boiled over. Reformers argued New Jersey needed a modern constitution and a governor strong enough to act. That’s where Alfred E. Driscoll came in.

Alfred E. Driscoll A Constitution and a Highway, 1947–1954

If one governor can be said to have invented the modern New Jersey governorship, it’s Alfred E. Driscoll. A Republican from Haddonfield, Driscoll wasn’t flashy. He was methodical, a lawyer’s lawyer. But he had timing on his side.

By the mid-1940s, New Jersey was booming with wartime industry and suburban expansion. Yet its government was still running on a 19th-century operating system. Driscoll led the charge for a new constitution, adopted in 1947, that gave the governor a four-year term, reorganized state courts, and crucially outlawed racial segregation in public schools.

That last piece mattered. This was seven years before the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education. New Jersey, often caricatured as a land of turnpikes and diners, quietly became one of the first states to constitutionally ban segregation.

Driscoll also built things. Under his watch, two projects changed the state forever the New Jersey Turnpike and the Garden State Parkway. They turned farmland into commuter belts, made it possible to live in Middlesex and work in Manhattan, and cemented New Jersey as a corridor state.

The governor’s mansion in Princeton still hangs Driscoll’s portrait with a quote about highways and constitutions. Together, they made him arguably the most influential governor of the 20th century.

The Swing to Culture Thomas H. Kean, 1982–1990

Jump ahead three decades, and the governor’s office was occupied by a man who loved poetry as much as politics. Thomas H. Kean, a patrician Republican with an old New Jersey family name, governed in the 1980s and left behind a legacy not of constitutions or roads, but of image and culture.

In 1982, Kean narrowly won election. Four years later, he won re-election with a staggering 70 percent of the vote still the biggest landslide in state history. His popularity rested on two pillars optimism and branding.

The most famous piece of that branding was the “New Jersey and You Perfect Together” tourism campaign. To outsiders, the ads with Kean’s gentle, almost professorial delivery were fodder for late-night jokes. Inside New Jersey, they worked. They gave the state a rare sense of pride at a time when “Sopranos”-style jokes and pollution headlines dominated its reputation.

Kean also poured money into the arts. The creation of the New Jersey Performing Arts Center in Newark wasn’t just about concerts and plays; it was an effort to revive a city battered by riots and disinvestment. He believed culture could be an economic engine. In Newark, that idea planted seeds that are still visible today.

On policy, Kean was quietly progressive for a Republican governor. He ordered state pension funds to divest from apartheid South Africa. He pushed for better funding for public schools. He spoke about racial equity in ways that foreshadowed the moderate Republicanism that would soon vanish from national politics.

By the time he left office in 1990, Kean was not only New Jersey’s most popular governor in decades, but a figure with national stature. President George H.W. Bush tapped him for education commissions. Years later, George W. Bush named him chair of the 9/11 Commission. In Trenton, though, he’s remembered as the governor who, for a brief moment, made New Jersey feel “perfect together.”

James J. Florio A Tax Gamble That Backfired, 1990–1994

When James J. Florio walked into the State House in 1990, the mood was grim. The economy was slowing, revenues were drying up, and New Jersey’s books were bleeding red. Florio, a Democrat and former congressman from Camden County, decided to confront the problem head-on.

In his first budget, he pushed through what remains one of the most controversial tax packages in state history $2.8 billion in hikes, including a doubling of the top income tax rate and an expansion of the sales tax. He argued it was necessary to fund schools and provide property tax relief.

New Jerseyans didn’t see it that way. Suburban voters, already reeling from high costs, staged protests. Editorial boards slammed the hikes. In 1991, Republicans stormed to control of the legislature in a wave election fueled almost entirely by anti-Florio anger. “Florio Free in ’93” bumper stickers sprouted on minivans from Bergen to Cape May.

The irony was that Florio’s fiscal discipline helped stabilize New Jersey’s finances. But politics isn’t kind to governors who ask too much of taxpayers at once. By 1993, his approval rating was under 20 percent. That fall, he narrowly lost re-election to a challenger who promised tax relief and little else.

Christine Todd Whitman First Woman in Drumthwacket, 1994–2001

That challenger was Christine Todd Whitman, a Republican from Somerset County who would become New Jersey’s first and still only female governor. Her 1993 victory over Florio was razor-thin fewer than 30,000 votes out of more than two million cast.

Whitman’s calling card was tax cuts. She pledged and delivered a 30 percent cut in income taxes, framing it as both economic stimulus and an antidote to Florio’s overreach. The move cemented her reputation as a fiscal conservative.

Her tenure was also a study in narrow margins. She barely won re-election in 1997 against Democrat Jim McGreevey, again by fewer than 30,000 votes. The closeness of those contests reflected New Jersey’s polarized electorate in the 1990s suburban moderates leaning one way, urban Democrats leaning another, with the balance shifting back and forth every cycle.

Symbolically, Whitman’s governorship mattered. She broke the gender barrier at the top of New Jersey politics, and she governed in an era when moderate Republicanism still had room in the national party.

But her story didn’t end in Trenton. In 2001, she resigned to become Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency under President George W. Bush. There, her reputation took a hit. After 9/11, she assured New Yorkers that the air in lower Manhattan was safe to breathe. Years later, she admitted those statements were premature and misleading. For many, that tarnished what had been a historic career.

Chris Christie From Sandy Hero to Bridgegate, 2010–2018

Skip ahead a decade, and New Jersey had another Republican governor one whose national profile would eclipse all others in recent memory. Chris Christie, elected in 2009 after a stint as U.S. Attorney, relished confrontation.

Christie campaigned on taking on public unions and reining in what he called “out of control” spending. Early in his tenure, he struck deals to reform pensions and public employee benefits. He was loud, brash, and made national headlines for YouTube clips of town hall confrontations. For a while, that blunt style was his political brand.

Then came Superstorm Sandy in 2012. Christie’s response hugging storm victims, walking devastated boardwalks, appearing alongside President Barack Obama just days before the presidential election made him a bipartisan symbol of competence. His approval soared above 70 percent. For a brief moment, pundits crowned him the future of the Republican Party.

But politics is unforgiving. By 2013, Christie’s team was caught in the “Bridgegate” scandal, accused of orchestrating traffic jams on the George Washington Bridge as political payback. Christie denied involvement, but two aides were convicted. The image of Christie as a no-nonsense reformer collapsed into a narrative of bullying and abuse of power.

By the time he left office in 2018, his approval rating hovered in the teens. National ambitions fizzled. His arc from Sandy hero to scandal casualty remains one of the most dramatic rises and falls in New Jersey political history.

Phil Murphy A Progressive in a Cautious State, 2018–Present

Into that void stepped Phil Murphy, a Democrat with a background unusual for New Jersey politics. A former Goldman Sachs executive and U.S. ambassador to Germany, Murphy sold himself as a progressive outsider with the resources to take on entrenched interests.

He entered office in 2018 promising to make New Jersey “stronger and fairer.” His agenda has included:

- Raising taxes on the wealthy and corporations.

- Expanding property tax relief through the ANCHOR program.

- Aggressively promoting renewable energy projects, including offshore wind.

- Investing in startups, brownfield redevelopment, and historic preservation.

- Expanding paid family leave and other equity-focused programs.

Critics, especially Republicans like Jack Ciattarelli, argue that Murphy has made the state less affordable, driving businesses and families out. But Murphy scored a historic achievement in 2021 he became the first Democratic governor re-elected in 44 years.

That win suggested that despite grumbling over taxes, voters were more comfortable with his brand of progressive leadership than pundits expected. In some ways, Murphy has positioned New Jersey as a laboratory for left-of-center governance in a suburban, diverse state. Whether his policies are sustainable long-term is a debate that will shape the next elections.

The Cycles of New Jersey Politics

Looking across the decades, a rhythm appears in New Jersey’s governorships bold reform, voter backlash, a swing in the other direction.

- Driscoll expanded power and built infrastructure, and was celebrated.

- Kean emphasized culture and bipartisanship, and soared in popularity.

- Florio raised taxes, and paid the price.

- Whitman cut taxes, and squeaked by.

- Christie rose on crisis leadership, then collapsed under scandal.

- Murphy has embraced progressive spending, testing the limits of voter tolerance.

This back-and-forth reflects the state’s makeup. New Jersey is split between wealthy suburbs, post-industrial cities, and rural southern counties. No single political ideology dominates for long. Every governor since the mid-20th century has had to navigate that tension.

What Comes Next

Murphy, now in his second term, can’t run again in 2025 under current rules. That opens the field. Republicans, led by Jack Ciattarelli, see an opening by hammering affordability. Democrats will likely try to defend Murphy’s gains while appealing to voters weary of taxes.

The legacies of past governors loom large in those debates. Every candidate remembers Florio’s backlash. Every Democrat studies Murphy’s surprise re-election. Every Republican invokes Kean’s bipartisan appeal. And every strategist warns against a Christie-style flameout.

In that sense, the history of New Jersey governors isn’t just history. It’s a guidebook sometimes a cautionary tale for anyone hoping to sit in Drumthwacket next.

A State Shaped From the Top

When outsiders think of New Jersey, they might picture turnpikes, diners, or Sopranos-style stereotypes. But for residents, much of the state’s identity has been molded by its governors the highways Driscoll carved, the cultural pride Kean nurtured, the tax wars fought by Florio and Whitman, the storm images of Christie, and the progressive agenda Murphy is still trying to write into law.

From Livingston in wartime to Murphy in an era of progressive ambition, New Jersey’s governors have been less caretakers than experimenters. Some gambled and lost. Others left institutions that endure. All of them, in one way or another, defined what it means to govern a state that is small in size but outsized in influence.

New Jersey Times Is Your Source: The Latest In Politics, Entertainment, Business, Breaking News, And Other News. Please Follow Us On Facebook, Instagram, And Twitter To Receive Instantaneous Updates. Also Do Checkout Our Telegram Channel @Njtdotcom For Latest Updates.

A political science PhD who jumped the academic ship to cover real-time governance, Olivia is the East Coast's sharpest watchdog. She dissects power plays in Trenton and D.C. without bias or apology.